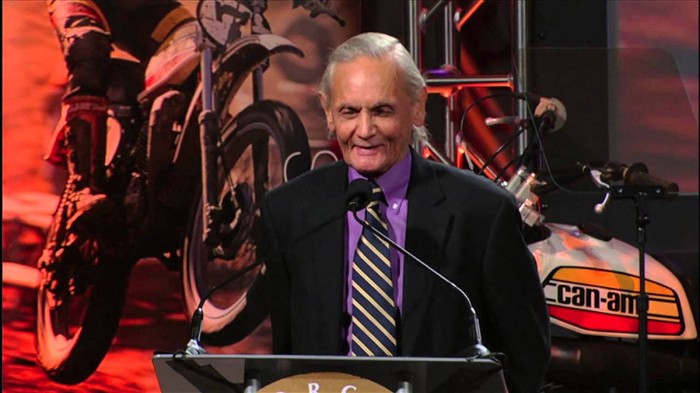

Racing's great and good were paying tribute yesterday to one of its great characters, Nobby Clark, who died on Sunday. As former world champion Kel Carruthers put it, 'Not many mechanics become famous, but Nobby was'.

The apprentice who followed his workmate on the Rhodesian Railways, Gary Hocking, to Europe ended up as the choice of champions with the names of 15 world title holders on his calling card.

As Carruthers described it, “When we were putting the Kenny Roberts Yamaha team together, he asked who we were getting as mechanics? Nobby was first on my list.”

Hocking’s impact on the European racing scene was little short of sensational moving from Reg Dearden Nortons in 1958 to riding, and winning, on works MZs and MVs in the succeeding three years. He invited his friend Nobby to join him at MV and that’s where the Rhodesian’s career as a works spanner man started.

But Hocking’s career with MV was short lived. He won the 500cc world championship in 1961, a TT in 1962 but walked out following a spat with Count Agusta over the provision of bikes for the post-TT at Mallory Park. He returned to Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), took up car racing but was tragically killed later that year in an accident that was never fully explained. But Nobby was out of a job.

Honda had already arrived on the scene and their introduction of the 250 four in 1961 saw Mike Hailwood win the TT on a privately entered model and Jim Redman the Belgian Grand Prix. Redman took Nobby on, he was noticed by Honda and in 1963 he became the only foreigner in an all-Japanese team. It was the start of a long and successful career in works teams with his ability to speak Japanese, Italian and English fluently with one or two others thrown in being a great help.

Hailwood had signed up for MV, the start of a rivalry with Hocking, but Nobby got on well with him. It was to prove valuable for both when Hailwood joined Honda in 1966.

Pauline Hailwood said, “Mike trusted Nobby. When Honda pulled out of racing in 1967 they gave Mike three bikes for private meetings and Nobby looked after then. In fact, he lived with Mike in Heston and they had a garage round the back.”

Stuart Graham, who joined Honda in the mid-sixties as a replacement for an injured Redman, said, “It was all new to me and Nobby was such a great help as a conduit/interpreter with the rest of the team. He lived life to the full, truly a free spirit and a great man.”

Paul Butler, for many years top racing executive with Dunlop, Yamaha and, more recently, Race Direct or MotoGP, said, “Nobby had the reputation in recent years of being a tuner but, in fact, his strength was his experience and immaculate preparation. This, in turn, created confidence for the riders he worked with.

A good story was when he and Gerry Wood were wrenching Rodney Gould’s 250 Yamaha at Spa. Rodney had changed every setting on the bike before the final free practice but was still unhappy. He went off to his caravan for the night leaving Nobby and Gerry with several hours work. They said “screw it” and adjourned to the Moderne in Francorchamps. The next morning Rodney came in after a few laps on the untouched bike with a smile saying, “I told you those changes would sort it.”

The relationship with Messrs. Hailwood and Butler would be renewed in the famous comeback in 1978 when both Ducati and Yamaha were the machines and Clark was the spanner man.

Recalling his time as a privateer in the sixties/seventies, Paul Smart said of Nobby, “I think it was at the Hockenheim GP in the late sixties when I first met Nobby. I was struggling to compete and Nobby could see I badly need help and offered his assistance which resulted inme getting on the podium. Just to talk to a man of his experience who was working for the best rider in the world, Mike Hailwood, and on the most exotic bikes in the world gave me a massive boost”.

And the post-race parties with Nobby, Mike and other great characters like Gerry Wood were something else. I got to know him quite well when Mike and Bill Ivy were great friends as Bill was a great friend of mine. Nobby was always happy whether he was working on a G50 or a Honds six. He had some amazing stories to tell – I only wish he had written his life story, even the naughty bits!”.

Bob Heath, now spending much of his time in Australia, called from Melbourne to recall when he had asked for Nobby’s help for the 1989 TT where he was riding an RG 500 and a TZ, “I was in awe of this man when I rang him and was amazed when he said ‘Yes’. He told me he didn’t profess to be a tuner. But could put things together properly. He joined in with our little team, lived with us in a house near Ballaugh and I finished third behind Hizzy and Graeme McGregor. He made the difference.”

The list of riders, representing the world’s greatest teams, who received the benefit of his attention was indeed a “Who’s Who” of racing: Gary Hocking, Jim Redman, Mike Hailwood, Luigi Taveri, Ralph Bryans, Stuart Graham, Kel Carruthers, Rodney Gould, Ken Andersson, Jarno Saarinen, Barry Sheene, Giacomo Agostini, Kenny Roberts, Marco Lucchinelli, Phil Read, Bill Ivy etc.

Of them all, Hailwood remained his favourite and to the end a rider he regarded as the greatest of all time because of his ability to win on any circuit and the least likely to invent excuses. But his admiration of Valentino Rossi was huge and he admitted it was a close call.

In his latter years, Nobby spent much of his time in America and in 2004 took out US Citizenship. In 2012 he was inducted into the AMA Motorcycle Hall of Fame – an award generally reserved for great riders – which was history in itself. But absolute history was achieved when the honour was removed following a spat with Team Obsolete owner Rob Ianucci, when he was accused of theft. The subsequent uproar caused the award to be restored with full honours.

My last afternoon with Nobby

Derek Rollo ‘Nobby’ Clark spent his last years in a small town called Dover Plains, some 80 miles north of New York City. After his falling out with classic bike sponsor Rob Ianucci he worked for a local classic car dealer but still found time to visit many race events like Daytona and the Barber classic museum.

He lived in a small apartment, part of a large house owned by a remarkable women called Edie Wolf-Brown who treated him as part of their family.

In September 2016 I took the train from Grand Central in New York to Dover Plains, where I stayed overnight, and enjoyed a modest celebration of his 80th birthday. This was a man I had first met at Montjuich Park in Barcelona for the Spanish GP in 1966, enjoyed fun times off-track, in the heady days of the sixties and with whom I had kept in touch subsequently.

He was already having dialysis for kidney problems but apart from growing a beard and being physically thinner he was on top of his game, displaying an encyclopaedic memory which seemed to include the frame number of every Honda six every raced. And he was fit enough to travel abroad enabling him a few months later to visit his sister in Durban.

A year on, in November 2017, I made the same trip. This time to a rehabilitation centre in Pawling, a few miles away from Dover Plains. During that period his condition – a variety of cancer – had worsened and he was battling against weight loss. The beard had gone but the humour hadn’t. Nor his optimism. Surrounded by newspapers – New York Times every day – magazines and books he was on top of everything from MotoGP to US politics. And regularly taking phone calls from friends round the world.

During that period great support had come from Kel, Jan and Paul Carruthers who set up a fund in order ot help with US costs which can be considerable. They were helped by Alex George in the UK. On Sunday, December 17, came the inevitable phone call. A great man of racing, whose name will be remembered long after many world champions have been forgotten, had not woken up.